|

||||||||

CHAPTER VMARCHIONESS DEGNINON OF THE OSAGE

A ROMANCE OF HARMONY MISSION AND HALLEY'S BLUFF

In the spring of 1821 a devoted band of men and women, and some children, assembled at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, thence to take a long and perilous journey into the West -- to the very limit of civilization at that time. They were missionaries from Boston, and the New England states going out under the auspices of the "American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions." Some time prior to this a delegate from the Osage Indians of western Missouri had visited Washington, D.C, and it was learned that his people desired the missionaries to come among them: and as the spirit of missionary work was intense at that time in the New England states volunteers were soon found ready to go; and under the direction of the "board" the little band had assembled at Pittsburgh. A more heroic, self-sacrificing and devoted congregation of fathers, mothers and children than these devout Congregationalists never met in communion.

They prepared for a long, slow, and laborious journey. They purchased common keel-boats, stored them with provisions, and when all was ready shoved out into the beautiful Ohio river. Friends on shore waved them goodbye in tears, and more than one of the occupants of those queer old keel-boats wept at what they realized would be a long separation from friends and home if indeed, they should be spared to return. Down the Ohio, past the villages, towns and cities -- to Cairo; pleasant enough in the main, but before they reached the mouth of the Ohio one of the party, a brave-souled mother, sickened and died; and her body was laid to rest on a pretty mound near the shore, there to sleep until the last great call. Thence up the Mississippi to the mouth of the Missouri -- the "Big Muddy," the flood way of the rivulets trickling down from the snow-capped Rockies on their way to the peaceful Gulf of Mexico; thence up to the mouth of the Osage river, the most tortuous stream known to the geography of the nation; thence up the Osage, by slow and laborious man power, the keel-boats with their precious cargo of human life and provisions were pushed with long poles day after day, and week after week. But it was a brave band. Not a heart grew faint. They had work to do; and not more resolute than they, were the Pilgrim fathers from whose loins they had sprung.

The journey occupied about six months, and on the 9th day of August 1822, they lashed their boats, side by side, to an over-hanging water-birch a few yards from the village of the Osage tribe. This was about three miles up the Marais des Cygnes river from its junction with the Osage in the extreme western part of Missouri.

Here these devoted missionaries established "Harmony Mission," and began teaching and preaching; and here they patiently labored for the Master until the Mission was abandoned fifteen years later, when the Osages, Delawares and Kaws moved out into the limitless prairies of the further West. The teachers met with much apparent success and the little Indians learned English readily, and many of the older ones were converted by the simple preaching of the Word.

About the time the missionaries left Pittsburgh a young Frenchman left France for New Orleans. United States of America. He was a scion of the old nobility -- in the prime of life, vigorous, handsome, cultured and proud. His splendid physique was remarked by all who knew him. He was from southern France, with hair and beard intensely black, sharp, penetrating eyes which were a compromise between a lustrous brown and a piercing gray.

His father had been compelled to flee for his life during the Reign of Terror in 1793, when the young man above described was an infant in his mother's arms. He had no recollection of a father's face, or a father's smile; nor had the faithful mother ever heard from the father. For years she had been persuaded that he was dead -- perhaps upon the shores of France: else somewhere in the New World. All she knew was that he had told her he would try to make his way to America, there to remain until the unhappy reign of blood should cease in his beloved France.

Oh, how long that beautiful young wife and mother cherished the memory of his last fond embrace, and the tender caresses of the dimpled baby boy in her arms, their only child. There was no time for planning; flight, immediate escape, was the only course possible to avoid certain execution. The fury of the Revolution was at its height, and the soil of fair France was drinking up the noblest blood of the Kingdom.

The young Frenchman, whose name was Auguste Letier, had exhausted himself trying to get some trace of his father, and had almost come to the conclusion that he must be dead, as his patient mother long since had done. But one day while strolling along the wharf in an idle sort of way at Marseilles, he chanced to meet an old "tar," and soon learned that he had made repeated voyages to America and always touched at New Orleans. Upon inquiry the old tar said he knew one of their countrymen in New Orleans by the name of Letier, and that he was a fur dealer, and wealthy; but he could not recall his Christian name.

This passing incident reawakened the young man's hopes of finding his father, and after relating the story of the old tar to his mother and getting her approval, he set sail at the first opportunity for America.

On his arrival in New Orleans he found the establishment just as the old tar had told him, but no one answered to the description given him by his mother. The place was in charge of his countrymen, and without disclosing his own identity he learned that the proprietor, Ignatius Letier, was in truth his father. He learned, also, that he had gone up the Mississippi only a few weeks before on one of his annual trips to the fur dealers at the settlements along the river, and that he was sometimes absent on these trips for months. He usually went as far north as St. Genevieve, Missouri, and sometimes as far as St. Louis.

The method of transportation upon the Mississippi in those days was unpleasant; but in autumn the weather is fine and Auguste set out at the earliest moment for St. Genevieve, and upon his arrival there learned that his father had gone on to St. Louis. So, after a day of rest and real enjoyment in the pretty French village, he started for St. Louis with a light heart and pleasing reflections. But at St. Louis, to his chagrin, he learned that his father had gone into the interior to visit some French fur dealers, and no one could tell just where. Auguste went to Jefferson City, and there learned that a man answering the description in his inquiries, in company with two others, had gone up the Osage river to buy furs at Harmony Mission.

It was, by this time, late in the season; the Osage was swollen, and progress was slow, and on the evening of the first day of January 1822 the boat was lashed to a convenient root for the night, and the party prepared to camp on shore. For days they had rowed against the rapid current through a rough and unbroken wilderness; not a human being visible in the endless forests along their solitary journey. As they were preparing supper to the great surprise and joy of Auguste Letier, a gentleman of his own country visited their camp. After the ordinary French civilities mutual inquiries were indulged, and Auguste learned that his visitor's name was Melicourt Papin, formerly of St. Louis, and a settler of several years of that vicinity. Further inquiry revealed the fact that Monsieur Ignatius Letier of New Orleans, a fur dealer, had arrived upon that very spot -- known on the river as "Rapid de Kaw"-- two weeks before a very sick man; that Monsieur Papin had taken him home with him, where he, his good wife, and the Mission doctor, had cared for him the best they could. But the fever raged without abatement, and on the 25th day of December -- Christmas day -- his spirit returned to Him who gave it. As Monsieur Papin paused in his sad recital Auguste, though brave-hearted and strong burst into tears and wept like a child, for some moments no one disturbed him; then he said, "Monsieur Letier was my father. He was compelled to fly front France when I was a babe in my mother's arms. I came here in search of him."

Auguste spent a restless night. The blow was so sudden that it was a shock. It came at a moment when his brightest anticipations were about to be realized as he had dreamed and dreamed. Early the next morning he went to the little log cabin of Melicourt Papin, a rude hut in exterior, contrived from trees felled in the immediate forest, but within was comfort and happiness; for the deft hands of a cultured housewife made amends for the shortage of things usually found in the homes of the civilized parts of the country. It was an ideal pioneer home, in a forest so dense and magnificent that the Dryads might have envied a residence there. After a wholesome breakfast on corn-bread and wild meat, and rare rich milk, Melicourt and Auguste visited the grave of Ignatius Letier. It was situated on a beautiful knoll some distance from the fretful Osage and above its wildest floods. Here in the solemn and voiceless woods, beside his father's grave, Auguste told Melicourt the story of his long and fruitless journey to recover a lost father; and somewhat of his history.

The two men were ever after friends, and Auguste was an honored guest at the comfortable home of Monsieur Papin.

The companions of Auguste returned in a few days to St. Louis. It was now mid-winter in that western country, and the hope and life had gone out of the young man. But he concluded to await the coming of spring to start on his return voyage to France, via New Orleans, and at the earnest solicitations of Monsieur Papin made his home with him. For days and weeks he sorrowed for his father, becoming more and more despondent. But one fine winter day Monsieur Papin prevailed upon him to go with him on some business with the good missionaries to Harmony Mission, only two or three miles up the Marais des Cygnes river, near the mouth of "Mission branch." The Marais des Cygnes and Little Osage rivers form a junction about a mile from the home of Melicourt Papin and here is the head of the Osage river proper. From its junction with the Little Osage the Marais des Cygnes marks a tortuous route to the northwest, and has its origin away out in the prairies of the then uncivilized Territory of Kansas.

They spent a pleasant day with the missionaries and their families in and about their rude pioneer homes; and on their way and while in the Osage village Auguste had his first introduction to the red men of the forests and of the plains; for while the Osage tribe had for ages made their homes in the forests along the rivers, there were in this village quite a number of Kaws and Pottawatomies who had come down from treeless and trackless Kansas. He, also, met here French fur traders who had trafficked with the Indians for years, making several trips up and down the Osage and Missouri to and from St. Louis, which was then, as now, the great metropolis of the Mississippi valley. Some of them had homes among the peaceful Osages, and history fails to tell just when the first French fur dealers settled among the Osage tribe.

Game abounded in the splendid forests along the rivers. Deer, antelope, coons, squirrels, turkeys and prairie chickens were all within easy reach on the land, and on the waters wild geese and ducks of every variety known to the hunter. Monsieur Papin had two faithful, intelligent dogs, and was provided with guns and ammunition in abundance, a regular frontier outfit for that day and generation; and in order to divert Auguste's mind from his great sorrow they spent much of the pleasant winter weather hunting.

Under this sort of wild and exhilarating sport Auguste soon became himself again and enjoyed life to its utmost; but in the midst of his new experiences he never forgot his father, and that his solitary resting place might not be forgotten, nor obliterated, he found time to quarry, cut and erect, as best he could with the rude tools at his command, a stone monument at his grave. The inscriptions were few but they were cut so deep and plain they can be easily read today. On the front and smoother side of the stone, which stands about six feet high, may be read --

Ignatius Letier, Marquis.

Born in Marseilles, France, 1770.

Died on the head-waters of the Osage river, near Harmony Mission,

State of Missouri, U.S.A.

December 25, 1821.

Erected by his son, Auguste Letier.

The winter passed. The early spring work of Melicourt Papin, who was engaged in a sort of agricultural life, demanded more and more of his time and attention: so that Auguste was left more and more on his own resources for amusement. Time began to hang a little heavy, and he began to talk of his departure; but the cheerful wife of Monsieur Papin urged him not to hurry, assuring him that the voyage would be much pleasanter later. The picturesque scenery on the journey down the Osage would then be really delightful; the full leafed forests, and the warm, soothing sun-rays in May or June this latitude would, she urged, make an otherwise forbidding voyage a real pleasure.

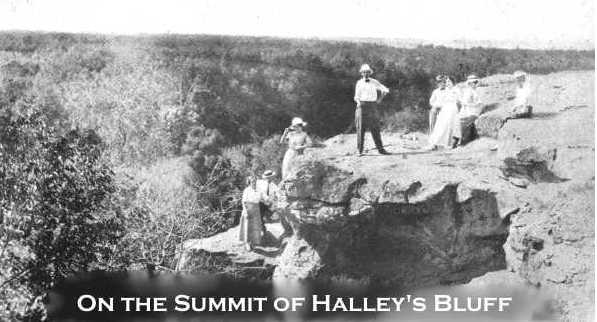

No word had reached him from his mother, nor could he tell whether any of his letters had reached her. That, when he thought of it, worried him a great deal. But he hesitated and lingered. The wild fowls had abandoned their haunts on the lakes and rivers and the season for game was over. But he had learned from Monsieur Papin that the Osage and Marais des Cygnes abounded in game and fish. So on a beautiful warm day in May he took his gun and rod and strolled down to the river, thence up its shaded shore a mile or two to a point opposite some immense and picturesque cliffs which rose from the water's edge, nearly perpendicular, about two hundred feet. It was an inspiring scene and he wondered why Melicourt had never spoken of it, nor taken him to see it. The Osage at this point was and is very narrow and deep, apparently having cut its way into the very roots of this gigantic stone barricade on its short and fretful sweep around this unexpected obstacle. Nothing but the chirping of birds and the solemn hush of the forest disturbed his meditations as he sat for some time on an old pecan log, waiting for some member of the finny tribe to excite his attention by a "nibble." He studied the scene before him in a pleased and lazy sort of manner, and became more and more anxious to cross the river and explore some of the cave-like places and recesses he could see from his position; when suddenly, quietly, there appeared around the cliff and beneath its awful over-hanging stones, a striking female figure -- a young Osage "squaw," as he finally concluded; but at the moment he was distracted by an ugly pull on his rod, and by the time he had successfully landed a ten pound "Buffalo," and got his breath, the "squaw" had disappeared.

Auguste returned to the Papin home, having enjoyed a pleasant day and with much talk for Madame Papin. The momentary glimpse of the beautiful "squaw" had photographed her face and figure on his mind and these would not be put away. That night he saw her in his dreams. He talked a great deal to Madame Papin about the Indians, recurring again and again to the "squaws" as they were called. He visited the village day after day for some time, and he liked to hear Madame Papin tell of the young "squaws," and dilate upon their bravery, strength, and social habits, if indeed they could, in a state of nature, be said to have any "social" quality.

But Auguste never told Madame Papin of the fleeting vision up at "Halley's Bluffs," nor of the form and figure that haunted his slumbers night after night.

Auguste, Melicourt and Madame Papin often sat, in the warm spring evenings on rude benches contrived beneath the stately pecans and wide spreading elms, whose dense foliage was a real comfort in summer and a protection to their humble home when the rude blasts of winter swept down upon them from the treeless prairies of the Northwest. These great kings of the primeval forests were from four to five feet in diameter, and stood more than one hundred feet high. They struck their roots deep into the richest soil to be found in the world. Plenty of moisture from below and rain and sun light from above, during years and ages past, had developed along these rivers a race of majestic pecans, elms, walnuts, sycamores, hickories, hackberries, and birches. All these varieties stood in stately grandeur about the home of the Papins. These trees spoke their own language to these children of France and they were loved and enjoyed by those who had made their home beneath their protecting branches. Here they enjoyed to the uttermost the undisturbed expression of Nature as she towered above them, reflecting the lights and shadows of the setting sun in May, or as she lay spread out before them along the Osage and the Marais des Cygnes, and on the limitless prairies to the northwest. Here they talked of France -- of the cruel days of '93, of Robespierre, Danton, Mirabeau, and the great Napoleon Bonaparte; and here they talked of the missionaries and the children of the Osages, whom the good missionaries had left comfortable New England homes to rescue from ignorance and sin. Melicourt Papin was a student of the Indian character and habits. From him, in these delightful evening chats, Auguste learned that chastity and social virtue were not among the striking and admirable characteristics of the females or "squaws." But the squaws of the Osage tribe were industrious, patient, heroic, of splendid physique, and more regular featured than the other tribes in that section of the West. They were straight as an arrow and as graceful as the wild swans on the waters of the Marais des Cygnes, from which, by the way, the river takes its name, Marais des Cygnes, meaning in Spanish, the river of swans or more literally a river of white swans. Unlike the Kaws and some of the other tribes who had dwelt upon the open, sun beat prairies for uncounted generations, their houses being in the dense forests along the rivers, the Osages were not so dark and swarthy in complexion, not so weather worn in appearance as the prairie tribe. And this characteristic of their appearance was much more marked in the "squaws" than in the "bucks" or male members of the tribe.

From Madame Papin, Auguste had learned that there were some half breeds among them, sons and daughters of French fur traders, and that half breed "squaws" were strangely beautiful, having inherited much of the complexion, character and sprightliness of their French fathers. For years past the young scions of old and respectable French families of St. Louis had visited the Osages to trade and buy furs. On one of these trips a handsome young Frenchman, with plenty of idle time, spent months at the Osage village hunting. This was in the autumn of 1805, soon after the Louisiana purchase from Napoleon, by which all the French and foreign settlements in that vast territory became a part of the United States of America. During his stay among the peaceful Osages he was attracted by a comely young squaw who had become the wife of an old "medicine man" of the Kaws only a short time before, and by the usages of the tribe she was accorded many liberties. The old medicine man had gone on a visit to his old tribe away out on the plains of Kansas, to arrest if he could some contagious disease that was decimating that tribe. In his absence his squaw or wife and the handsome young Frenchman had become great friends and often hunted and trapped together. The old medicine man did not return as soon as expected and it was learned in a few weeks thereafter from some young Kaw bucks camped near Rapid de Kaw on the Osage that the old medicine man had gone among the tribe, ministering unto the afflicted without fear, until at last he was stricken with the contagion, supposed to have been what we now know as smallpox, and he died and was buried according to the rites of his own people.

The friendship between the medicine man's squaw, now his widow, and the handsome young French gallant soon grew into attachment, and the devotion and the evident admiration of the young widowed squaw was pleasing to the young hunter. He came to love her, not as he would have loved one of his own beautiful dark eyed country women in St. Louis, but as a child of the forest -- a product of Nature, and the longer he remained at the village the more her presence and admirable devotion seemed necessary to his life and happiness. So, with the approval of the chief, in lieu of that of a father long since departed to the "happy hunting grounds" and according to the simple ceremonies of the tribe he took her "to be his squaw," and she promised "to work for him." For a few weeks they lived much as the rest of the tribe, and the squaw-wife's care of "her hunter" was constant and beautiful. Life to the exuberant young Frenchman was like a day dream in a forest, or a play day amidst the wild flowers on the sunny prairies. Like all good Frenchmen he was an enthusiast, and he had about made up his mind never to return to St. Louis, or the white man's civilization, so rapturous was his life among the Osages; and he had become so fond of his patient, devoted squaw.

But before his Indian "honeymoon" had passed, peremptory orders from his wealthy father, who had received an inkling of the young man's pranks among the Osages from a returned fur trader, caused him to suddenly change his mind. It awoke him from a long, sweet dream. It was a rude shock. He thought hard, and said nothing. It ripped up his charming life. To disobey meant disaster -- of that he was sure. So the first opportunity he slipped away, promising and hoping to return, and was off down the Osage for St. Louis.

He never returned.

No pen can picture adequately the distress of the squaw wife when she realized that her "handsome hunter" had abandoned her. Not by outward signs and lamentations did she show her unspeakable grief; for it was one of the peculiarities of the squaws not to complain. Their philosophy, if they can be said to have had a philosophy of sorrow, was of the Stoic order. But the quiet smile, which she was want to bestow upon "her hunter" when she accompanied him on his hunts, or with which she greeted him on his return at night-fall was no longer a light on her countenance, and the piercing, sparkling black eyes were careless and sad. She went in and out among her people doing good to the sick and the helpless old, and tenderly assisting mother squaws in the care of their little "papooses." She hoped against hope: she longed in silence for the return of her hunter for weeks and months. She seemed specially kind to the little papooses, and by and by, while fondling one new-born, the bright but quiet smile of other days would steal over her sorrowful face, and the gleam of an anticipated joy was visible in her eyes. The reason for all this became apparent a short time afterward when she lay upon a bed of skins beneath a covering of furs, in her solitary wigwam, and at her breast, so cozy and snug, she held a tiny squaw papoose. She gazed into its wondrous eyes and fondled its little feet and hands; and the old light came back to her eyes, and a quiet, sweet smile played upon her face. Her long dream was over, but it was as if her handsome "hunter" had sent her a precious gift in memory of his promise, alas! never to be fulfilled.

The little papoose was named Degninon (pronounced Danino) from some fancy of its mother, and it grew into girlhood under her devoted care much like the other papooses did. But Degninon became a great favorite in the village both with the Indians and the French fur traders. Her father's handsome face, his carriage and poise, were striking in the child: indeed, so far had his personal characteristics been transmitted to the little one that the Osage features and complexion were quite absent. There was that about her that suggested a Mediterranean origin.

She passed into womanhood strong, well developed, beautiful. She was fond of hunting, trapping and fishing. She and her mother provided for their wants by these methods; and when the French fur traders would come, Degninon was always ready with her furs to drive an advantageous bargain with the stranger; and so by and by Degninon possessed the rarest assortment of valuable jewelry, necklaces and other personal ornaments to be found in the village. She seemed to have inherited this characteristic of her tribe, but it was supplemented by an instinct that told her, of all the sundry offerings of the fur traders, which were really valuable.

She was an expert with the bow and arrow, and could handle an old-fashioned flintlock with skill and effect. But her chief delight was with the rod during the seasons for fishing on the Marais des Cygnes and the Osage. On pleasant days she would wander for miles up and down these rivers as fancy moved her, all alone, fearless of harm, exulting in the beauties of nature, and in the enjoyment of buoyant health. She had never known sickness; care was a stranger; she loved her mother and the big forests and the rivers, and she learned music of the wild song-birds about her.

There is something fascinating about a mere glimpse of a pleasing object when a second glance is impossible. The impression is made, but no opportunity is permitted to scrutinize the object, the picture or "vision" which has momentarily arrested attention. Auguste Letier had experienced the exasperating effects of this principle when fishing that pleasant day in May opposite Halley's Bluffs. But in the intervening weeks, in his rambles about the country and among the Indians of the village, or the missionaries at "Harmony" he had been unable to see any female face and form that answered to his impression of the face and form of her who had so suddenly stood before him on the jutting ledge of rock on the opposite shore, and as suddenly disappeared while he struggled with the fish. One evening Madame Papin in a careless sort of way had spoken about a "most beautiful squaw at the village whose father was an early French fur trader;" but Auguste said nothing about his adventure at Halley's Bluffs; nor had he seen any squaw about the village that answered to Madame's description or to his impressions of the face and form that confronted him that May day. Unwilling to permit such a trifle to annoy, yet he could not put it entirely away from himself; and he felt himself urged from within to revisit the Bluffs.

So one bright morning in June, shouldering his gun with which, perchance, to kill a mess of young squirrels for Madame Papin, and with rod in hand he started out, as he said, for a day of quiet sport. He concluded to cross the river and stroll up to the Bluffs along the opposite shore. It so happened, instinctively or by unconscious design, if that be not contradictory, that he followed a sort of natural pathway upon a ledge of stone near the water and beneath the over-hanging stones of the towering cliffs. He followed around the Bluffs some distance before he came to a position from which he could see the big pecan log upon which he sat and fished some weeks before. As he strolled quietly along he became interested in the striking evidences of man's handiwork on the face and in the sides of the massive rocks, which seemed built by the Creator as a fortress against the mad waters of the Osage. While momentarily studying one of the many prehistoric caricatures deftly chiseled into the face of the solid stone his reverie was dispelled and his attention arrested by the sudden swish of a line and splashing of a five pound bass, snatched from its play-bouts in the swift running waters of the Osage by the dextrous hands of a young squaw. She had risen to her feet in her effort to land this beautiful game fish, and at the same moment, she became conscious of the presence of the stranger. There stood the "vision" of Auguste, only a few feet from him and a little nearer the water's edge, smiling at her success and the frantic struggling of this gamey fish. He hesitated a moment, and then addressing his "vision" as "Mademoiselle" he stepped forward and offered to release the fine bass and "string" it for her. With a good natured smile Degninon accepted his polite overture, and Auguste realized that she was the "vision" made manifest on the former occasion. They stood face to face with but the cliffs, the waters, and the forests to witness their mutual "first impressions." Dressed in the skins of animals from waist to the ankles, with a red and yellow striped, loosely fitted woolen blouse making up the balance of her apparel -- bare-footed and bare-headed, except a striking variety of wild flowers interwoven with her long, black, loosely flowing hair; features as regular as those of the best bred women of France; -- flushed with native modesty, and her wondrous, speaking eyes looking him fairly and steadily in the face, is it any wonder that Auguste Letier, an enthusiastic child of southern France, the son and heir of a Marquis, should feel the spell of her presence and the enchantment of this "beautiful squaw" of Madame Papin's description, now standing unembarrassed before him? In a perfectly natural manner Degninon looked into his eyes, and then measured him from head to foot, as she would have done any object of nature of sudden interest to her. She had no sense of fear and was less abashed than Auguste by this sudden meeting. They were both pleased by first impressions and Auguste, addressing her in his native tongue, was delighted to discover that she could understand and speak French readily. He told her of his fondness for fishing and explained that that was the object of his coming to that place. She confessed her delight in the sport. So their acquaintance began, without, conventionalities, and under rather romantic circumstances and amidst pleasing scenes. It was plain from her manner that he was a welcome companion in the sport; and so he unwound his line, baited both hooks, and finding a comfortable seat near hers, they flung out their lines, and sat down to fish and chat. In the interims of disengaging the black bass from the hooks Degninon talked of her life and adventures along the rivers and in the forests. They had a great run of luck, and before the mid-day sun reached their position and made it uncomfortably warm on the bare and unshaded rocks, they had "strung" all the fish they cared to carry to the village some three miles distant.

Auguste, at the suggestion of Madame Papin, had taken with him a large lunch prepared according to French methods by the skilled hands of the good Madame. But as Degninon was used to fasting on her long jaunts from breakfast until supper she had nothing for a mid-day lunch; and when Auguste insisted that she should share his she declined, but under his entreaties, and as she said, "to please Monsieur," she finally consented. It was a warm day and a drink of water with their lunch was desirable; but along the bluffs which extended up and down the river about a quarter of a mile in either direction from where they were there was no available water except the river. But Degninon was familiar with all the springs, as well as other interesting places for miles around, and she led the way to find water for their luncheon. Taking her course up the river they kept close to the water's edge until they had passed the base of the higher cliffs and there they came up into the timber on to a beautiful, level, moss-grown, flower-bedecked, park-like place. In the midst of this natural park a sparkling spring of refreshing mineral waters gurgled unceasingly; and here they found rude stone seats contrived by "bucks" and "squaws" who had visited this life-giving spring some time during the ages they had inhabited the surrounding forests and plains.

Here they lunched, and here they rested during the heated hours of the day beneath the protecting foliage of an unbroken forest. They talked, like children, of themselves: and unrestrained by any sense of impropriety Degninon told Auguste the story of her life to that moment as she had it from her mother, and as it has been told in these pages.

As the sun declined and the shadows lengthened a refreshing zephyr from off the prairies stirred the foliage, and made this real scene dream like and fairy.

They retraced their steps for the "string" of fish, their rods and Auguste's gun. He was not sure of the interest he hoped he had awakened in Degninon's heart; and lest she might disappear forever on reaching the village he asked her to return the next day and show him the many curious sights and ancient hieroglyphics about the Bluffs, of which she had told him; and to make sure of her return, in a bantering way, he suggested that they hide their rods beneath some obscuring rocks as a pledge to meet there on the morrow. She hesitated, but his eager eyes won and she agreed to do so. With a light heart Auguste arranged the string of bass so they could be carried and Degninon shouldered his gun, like the experienced hunter she was, and they were soon drifting down the rapid Osage in her canoe.

The sun was setting in a clear sky, and no sylvan scene was ever more beautiful, soothing and seductive than that about them. Language can not give it even a pardonable picture to the mind; nor can any pen untouched by the divine spirit of love, peace and joy convey to the reader the tender emotions of their hearts, now thoroughly aflame with the restless passions of a holy first love. Soon they had reached the birch-bark canoe in which Auguste had crossed the river in the morning and rounding to he lightly leaped into it, loosened its mooring, and with a few deft strokes of the paddles he landed against the opposite shore where he could get it the next day; and by this time Degninon had come along side so that as soon as Auguste had secured his canoe he stepped into Degninon's and in an incredibly short time, by her strength and skill, against a vigorous current, she shot the canoe into a secluded haven a short distance below the "Bluffs," and having secured it to the shore, with fish and gun through a pathless forest, Degninon leading the way, they were off for the Osage village at "Harmony." It was a long, sweet walk in spite of the luxuriant grass, tangled vines and under-brush.

A short distance from her mother's wigwam Degninon exchanged the gun for the string of bass, hesitated a moment, and was off without a word of parting. All that Auguste could say, as he watched her retreating form, was -- "Tomorrow!" and either Degninon or the echoing trees replied -- "Tomorrow!"

It was now late. The full moon was up, and Auguste was soon at home with Monsieur and Madame Papin. A kindly welcome greeted him; but so full was Auguste's mind and heart of other emotions that he scarcely replied to the motherly solicitude of good Madame Papin. He dreamed in sleep and slept in dreams that night; and Madame Papin noted an indefinable change in his eyes, an uneasy, inexpressible something in his manner the next morning at breakfast when he told her that he had become interested in the scenes about Halley's Bluffs and so had forgotten his fishing rod and tackle, and that he must return and get them. But she said nothing about what she had noted to Monsieur Papin. So eager was Auguste to get off that he slipped away to the river before she could wrap him a mid-day lunch.

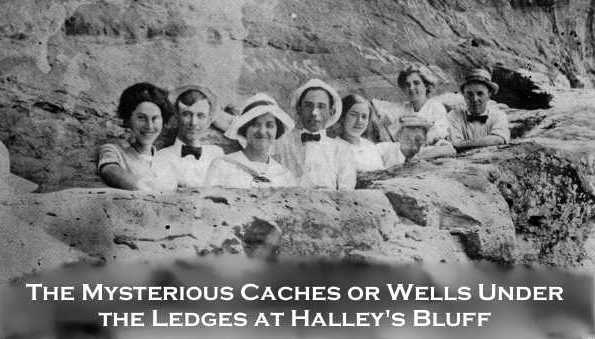

The distance from Degninon's wigwam to the river opposite the Bluffs was double the distance from the home of Melicourt Papin to the same point. But, Auguste was so eager and so fearful that Degninon would not keep her promise that he was early at the haven in which they had left her canoe; there it rested just as they had left it, swaying to and fro upon the waters; but a dreadful hush pervaded the forest and seemed to rest even upon the waters; the sun was just rising over the picturesque Bluffs; but, the scene did not appeal to Auguste as it once did. He could hear his heart throb. He had never experienced such emotions before; fear -- that she would not come -- hopeful expectancy, -- alternated in his mind. In this condition of mental agony he stood motionless, peering through the forest in the direction he thought she must come, but oblivious to all about him, and mistaken in the "points of the compass," the sudden snap of a dry branch directly at his back so startled him that he felt for the moment a real terror. Turning instantly, tremulous in every fiber of his being, he was face to face with Degninon, who smiled at his evident surprise. She suffered him to grasp her hands in both of his for the moments it required him to express in voluble French his extreme happiness and rapture. She had kept her pledge. He was in ecstasies. And she accepted his gallant care and assistance into the canoe with a graceful courtesy that was reassuring. It was a pleasant morning in the shadows of Halley's Bluffs and they at once began to look the curious old place over. They soon reached a height about one hundred feet above the water and above which the massive cliffs were perpendicular. At the point they had reached a great notch had been cut in the solid stone front as if by the ceaseless threshing of a fretful sea during prehistoric ages. This passage way, some ten feet wide and easily traversable. ran the whole distance around the Bluffs. Nature and the ancient waters, which had evidently spread out miles and miles beyond the confines of the river as it lay beneath them, and covered all the valley and low lands round about, had worn into the face of this stone fortress great rooms, some of them dark and uncanny.

All this must have happened long before human foot had trodden or human eye explored the country. And Degninon said the traditions of her tribe described the natural conditions of the Bluffs much as they were then and are now. They went into all the beautiful and curious places wrought out by the forces of nature. Auguste was often startled by the unsightly, weird and meaningless signs and figures of men and beasts cut into the sides of the stone. Many of these Degninon said, according to the ancient traditions of the Osages, were cut there by the servants of the "Great Spirit" in the ages long past. She said the traditions of her people taught that the figures of men in sitting posture were intended to teach obedience and subjection to the will and power of the Great Spirit. The caricatures of animals everywhere visible were intended, she explained, to remind the tribes of the good times to come in the "happy hunting grounds" beyond this life.

This was the significance -- this the philosophy of the prehistoric inhabitants of the country, and it had been handed down from generation to generation and it was an accepted tradition of her people.

So they talked as they passed on and on, examining every curious nook and cranny, every grotto and cataract, and overhanging flower; and suddenly, at the extreme point and bulge of the cliffs to the northwest where the "Bluff" stood out over them to its utmost, over the very river below, they came upon a series of wonderful pits or wells chiseled straight down into the solid stone. They were directly round, about five feet in diameter, and varied in depth from fifteen to thirty feet. They had evidently been cut with sharp tools of some kind, but tradition failed, Degninon said, to tell how it was accomplished. These wells were only two or three feet apart, back so close to the cliffs and so far under the overhanging bluff that no drop of water ever found its way into them. They were blackened on the inside as if fires had some time been builded in them, and being pressed to account for these really wonderful achievements of a race apparently long since perished from the earth, Degninon said she had heard her mother say that the old people of the tribe believed that these wells were digged out, by those who did it, for the purpose of curing and preserving the meat of animals taken in the chase; that when the meat was dressed it was hung by stout thongs tied to heavy cross-poles down in these stone holes to prevent wolves, bear and other carnivorous wild animals from getting it. This, she said, explained why the wells were blackened, for it was often necessary to smoke and cure it for use when on a long journey, or when fresh meat was unwholesome. This was all that tradition or story offered then, or has since offered, to account for these wonderful stone wells at Halley's Bluffs.

A pardonable digression may be indulged at this point. The writer recently visited Halley's Bluffs and examined those marvelous prehistoric wells and found eight or ten of them just as described in the foregoing. Nothing has ever developed to the writer's knowledge, to show when, by whom, how or for what purpose they were digged. No student of ethnology has ever been able to advance a more plausible story than the tradition related by Degninon.

By the time Auguste and Degninon had visited all the curious places, admired the mosses, ferns and delicate wild flowers clinging here and there, as lovers have done many times since, and the stalactite formations hanging from the roofs of the caves and grottoes it was high noon; but as Auguste had no lunch he said nothing. He had noticed a flat-like willow basket, evidently the work of her own hands, hanging from Degninon's shoulder, but he did not suspect it was a lunch basket. Such, in truth, it was. And it was well filled with some of the black bass they had carried home the evening before, together with other equally tempting things to a hungry man. Degninon's offer to share her lunch with him met with instant acceptance. Such is the frailty of man! So they clambered around and up a sort of natural stairway until they reached the very summit of the Bluffs. Here beneath a century-old white oak near the edge of the perpendicular cliffs where they could look out upon a beautiful scene as far as human vision could reach Degninon unpacked her willow basket and spread its contents.

All through luncheon Auguste talked in a delightful, easy manner of his pleasant, sunny France and told Degninon of his good, heartbroken mother, mentioning here and there, as they occurred to him, many incidents of his own life.

All this had the eager attention of Degninon.

The passion that bounded in her simple, innocent heart, was thrilling the heart of Auguste. And before the fragments of the lunch had been gathered up, and really without premeditation, urged on by every hope in his soul, forgetful of the indescribably beautiful scene stretched out before him, oblivious to all else earthy, Auguste gave expression to the secrets of his heart and laid before Degninon the hope of his life -- that she would become his wife and go with him to his mother in southern France and there be with him son and daughter to her in the disappointments and sorrows of her old age. No word escaped Degninon's lips. Her heart was throbbing. She felt for the first time the tumult of passion. Her simple, natural love had been awakened. She was radiant with the exaltation of the purest sentiments known to the human heart. And Auguste gazing into the depths of her speaking eyes knew the "beautiful squaw" of whom Madame Papin had spoken -- his "vision" of Halley's Bluffs -- was his forever.

No cruel doubt, no disquieting fear came into Degninon's heart. The response of her soul was so complete that nothing could have convinced or persuaded her that her love was not in accord with the wishes of the Great Spirit of her mother's people.

That night, in their wigwam, Degninon sat close beside her mother and frankly, innocently told her all. Her mother wept as she realized what it all meant to herself. The memory of Degninon's father was fresh in her soul. And her unfaltering love for the "handsome hunter" who had gone from her never to return was pleading in behalf of sweet Degninon then and there. She caressed and fondled Degninon as if she were indeed a little papoose again in her arms. She gave a mother's blessing and Degninon dreamed that night in her mother's arms, in fact, as when a papoose, and oh! such sweet, peaceful sleep came to rest her surcharged soul.

Underneath the stately trees near the dwelling of the Papins, with the flecking moonlight all about them. Auguste had a long son-like talk with Madame Papin, and the next day while on their way to visit a sick neighbor some distance down the Osage she told Melicourt the story of Auguste and Degninon. On their return he congratulated Auguste and offered his services in building the boat for his return voyage to France, now determined upon. For the next ten days Melicourt and Auguste were very busy men; but Auguste found time to spend his evenings with Degninon at her wigwam or at the hospitable home of the Papins. These delightful evenings are passed without comment. The reader is left to fill in the story at this point. It was merely the re-enactment of the old, old story.

By and by the boat for their voyage down the Osage, the Missouri, out into the Mississippi, thence to New Orleans, was ready, good and stout.

Auguste had secured the necessary proofs of the death of the Marquis, his father, and the day for the wedding and departure was settled. Melicourt had spoken to the Rev. William B. Montgomery, one of the good missionary preachers at the "Mission."

At the appointed time Auguste and Degninon stood within the rude walls of the first school house erected by the missionaries at Harmony, and there in the presence of the Papins, the mother of Degninon, a few Osage "squaws," and all that little band of devoted missionary workers the Rev. Montgomery repeated the simple words and took the responses that made them one forever in life and love and in the laws of God and man.

It did more than that -- it made Degninon a Marchioness of France: for upon the death of Ignatius Letier his only child, Auguste, succeeded to the father's estate and title.

The marriage of a Marquis of France to beautiful Degninon, was a great event in the annals of Harmony Mission and it has its place in the history of one of the first efforts to Christianize and civilize the Indians on the western frontier.

We shall not follow the Marquis and Marchioness Letier on their romantic bridal tour down the rivers to New Orleans, thence to the far-away sunny France. Our story is told. It may be said in passing that they reached their home in France in due time, where they were received by the good mother as lost, loved children returned, and where they lived to a ripe age, as devoted to each other as when their hearts were united on that day in June beneath the great white oak on the summit of picturesque and eternal Halley's Bluffs and that today there flows in the veins of some of the greatest and grandest men and women of Republican France the blood of Madame Papin's "beautiful squaw."

|

||

Bates County Missouri MOGenWeb |

||